How on earth does one distill hundreds of archival boxes containing letters, meeting minutes, conference notes, photographs, surveys, legal documents, and even the occasional poem into a succinct historical timeline of the Federation from 1940 to the present day? This is exactly the question we explored during this past summer of 2015. First, who are we? We are two Masters of Public History students from Carleton University in Ottawa. Thomas is doing research on board games and Rob studies relationships between sound and memory. In May we began to pour over hundreds of archival boxes from the Federation’s genesis as two separate research councils —one for the humanities and another for the social sciences — right up to their amalgamation in 1996.

Of course, important historical moments such as the founding of the Canada Council, the creation of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), or the amalgamation of the social science and humanities secretariats were waiting in the prose of typed and handwritten letters and meeting minutes. But layered throughout the vast information held in these boxes were important historical anecdotes — short and simple, yet never mundane. Like the different up and coming names getting a foot in the door. Distanced from their popular memory or great works we find their routine correspondence. For instance, amongst dozens of letters lies a simple cheque addressed to Pierre Trudeau for helping to edit a manuscript. As Prime Minister, Trudeau later oversaw the creation of SSHRC. There was also a correspondence from the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) commenting on a bright young thinker who could one day be a ‘big name’. That person was the Canadian philosopher George Grant.

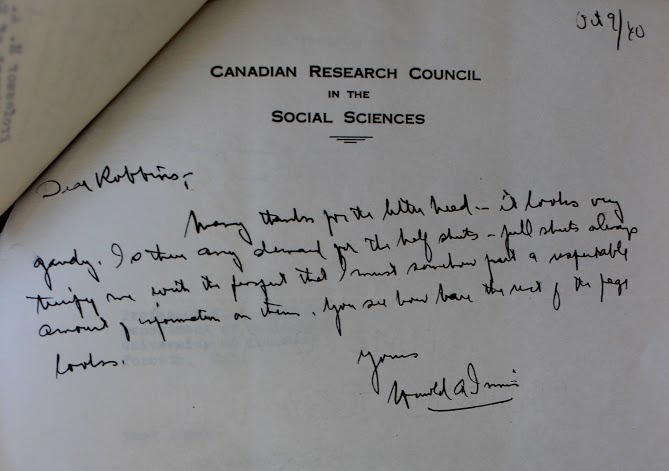

We also learned the fallibility of big names in research. Harold Innis, a co-founder of the Canadian Social Science Research Council painfully chose to handwrite correspondence. We spent hours trying to make sense of Innis’s scribbles. In fact, in 1947 SSRC secretary John Robbins commented to a friend on the ridiculous illegibility of Innis’s handwriting. Apparently, we were not alone.

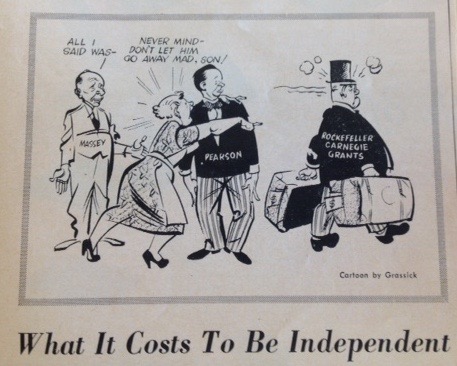

Although important Canadian figures write themselves in and out of the historical archive, the habitual, everyday activities of the secretariats and its members ensured the Federation’s survival and prosperity. They met years of funding woes with continual lobbying efforts; they worked tirelessly to promote and publish Canadian academic research; they developed communication projects in radio and print media to increase their public representation; they organized annual meetings of academic societies across Canada to bring researchers together. They created, then, a community for the social sciences and humanities in Canada.

One of the overarching observations that can be made about the Federation’s history is how enduring and consistent certain core preoccupations have been—including the concern for making the case for the value of these disciplines and the constant struggle for resources and recognition in the halls of power. Correspondence over the years, whether dated 1940, 1957 or 1996, hits similar notes yet remains contingent upon specific historical facts. Another common thread is the consistent rallying power and commitment of the Federation and its predecessors in mobilizing the community. On this 75th anniversary, then, we all have an opportunity to reflect on this rich and important history — to understand how integral the Federation was and continues to be for research in the social sciences and humanities, as well as the voice it has provided researchers for decades.

Our work on this project taught us valuable lessons about historical research. Practically speaking, we learned to tell stories by distilling unfathomable amounts of paper into a timeline. But we have only scratched the surface. Textual archives are incredible resources of potential knowledge. Yet other forms of historical research - namely oral interviews - hold the promise of a more thorough story. To put it humbly, the story we tell pales in comparison to the stories waiting to be heard. As always, there is much more work to do.